“New perspectives” born from daily experimentation. Taking a look at the shape of contemporary design that “we+” aspires to.

“New perspectives” born from daily experimentation. Taking a look at the shape of contemporary design that “we+” aspires to.

Contemporary design studio we+ moved to their new office in Nihonbashi Yokoyamacho. Their approach of reconstructing things from new angles with the concept of “offering alternative options to society” has received high praise both domestically and internationally. Their production process, which they have described as being akin to an “elementary school science experiment,” is closer to that of tried and tested craftmanship and how it finds its essence through trial and error.

Today we’re speaking to co-founders Toshiya Hayashi and Hokuto Ando about the realities of their creative activities and the challenges they would like to take on in the future.

There is a new approach even for the chair. The value created by contemporary design.

-To begin with, could you tell us about how “we+” was established and what kind of business you do?

Hokuto Ando (hereinafter referred to as Ando): Hayashi and I met through a mutual acquaintance when we were in college, and the three of us teamed up in around 2007 and started engaging in creative activities. At the time, we all took on our own side projects while working our respective regular jobs. After some time, our mutual friend pulled out, and creative activities became quite busy. “This is no longer a side project. We should make it our main line of work” was the sentiment from which “we+” was launched. This was back in 2013.

Hokuto Ando. Graduated from Musashino Art University before moving to London. He is involved in multiple disciplines ranging from concept development/strategic planning to general design.

Toshiya Hayashi (hereinafter referred to as Hayashi): We style “we+” as a contemporary design studio, and as such we place great importance on creating new value through design. While functioning as a studio that designs products requested by clients, we do our own side projects, we involve ourselves in product and space design utilizing R&D elements. I think having this vast toolset for expression is what makes us unique.

-Could you tell us more about contemporary design and its concepts?

Drought (2016) Photo: Masayuki Hayashi

Ando: We view contemporary design as “another perspective,” a slight deviation from what already exists. A design that captures what it is trying to express.

This chair may be an example that makes it easy to understand. Chairs are an orthodox piece of furniture that has been around for a long time, right? Their function is to be sat on or to display authority. Its shape and materials are considered based on a variety of requirements which have led to how we typically imagine a chair to be. But, aren’t there other approaches we can take to the pre-existing concept of the chair? Aren’t there forms of expression that could change that concept? This particular piece was the product of that line of thinking.

This chair was made from a combined mold of wax and water absorbent polymer. After covering the polymer mold with wax and drying/solidifying it, the polymer shrinks to about 10% of its size. Drying it further causes the wax to peel off, creating its characteristic design. Finally, we replaced the wax with bronze to complete the chair.

In other words, no one knows what shape it will ultimately solidify in, which in a sense means it can be seen as a shape created by natural phenomenon. Also, the slow pace at which it comes to form gives the product a timeline, creating the connotation of questioning the pre-existing concepts of the chair with ideas like “natural phenomenon” and “time.”

-Now that you bring that up, it feels like a lot of products from “we+” involve natural phenomena like water, sand, or wind. Is there a reason why you pursue creativity in such natural things?

Hayashi: I think there is no expression more powerful than nature, and that using natural phenomena when expressing something is the most effective way of reaching people’s hearts. This is the main reason why we include natural elements in our works.

Humans have evolved to stand against the power of nature and have adapted to live in harmony with it as well, so it can be said that the history of humans is also a history shared with nature. It’s as if it’s carved into our DNA, which is why I think it’s only natural our hearts are moved when we see beautiful scenery or the like.

Natural phenomena are of course wonderful the way they are, but with the application of a little control, I felt that phenomena that go beyond nature could be created. For example, droplets of water on the tips of leaves fall at random, but how would it feel to witness them all dropping in unison? Things like that. We thought that by creating different perspectives on control, we could move the hearts of people who view our work.

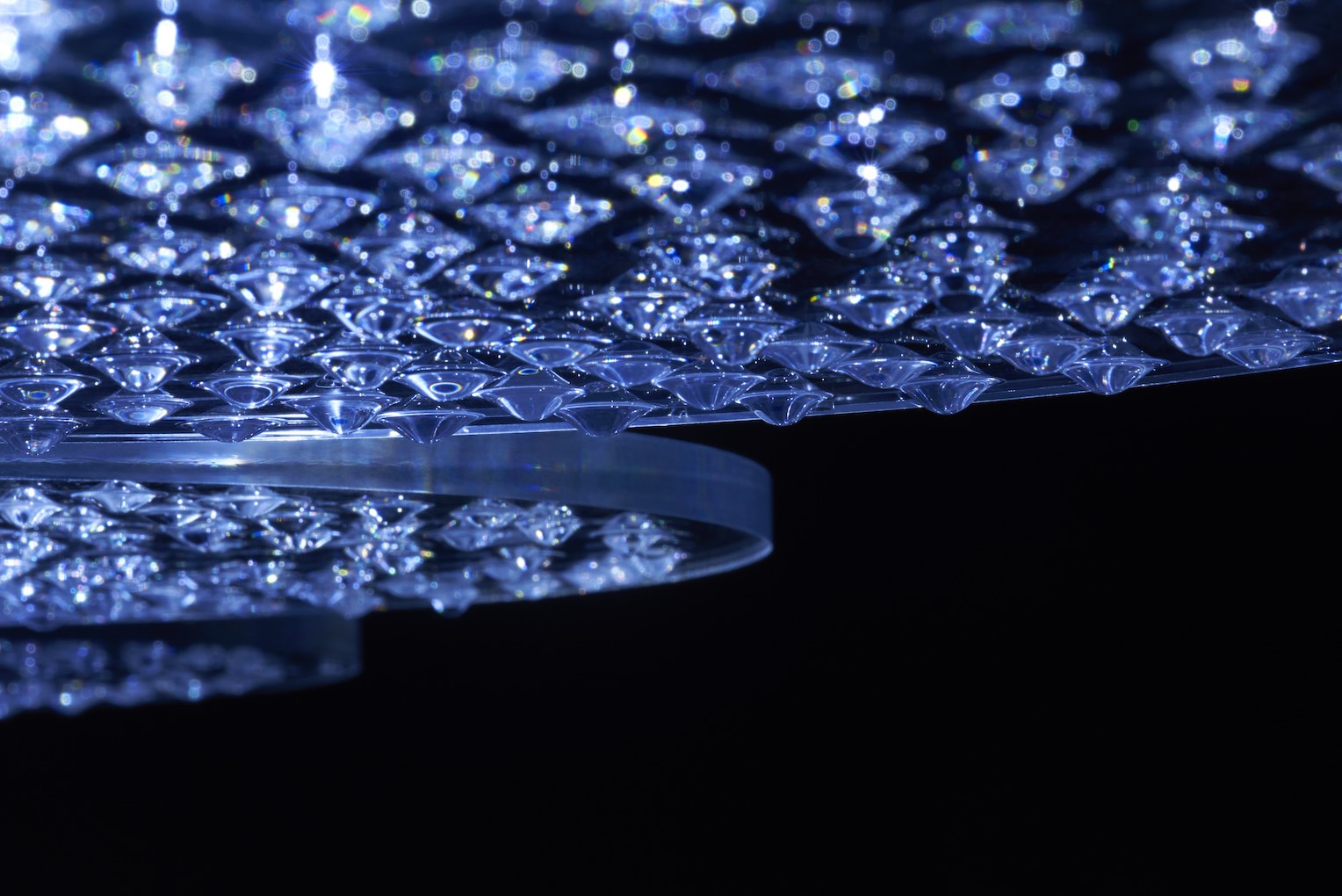

Cuddle (2017) A piece using the natural phenomena of water droplets. Photo: Masayuki Hayashi

Toshiya Hayashi. Background in advertising. Not limited only to artistic approaches, he is well versed in a wide variety of areas from branding to communication strategy.

Ando: In addition to that, if we are going to create things, we want them to be relatable, we want to pursue the extent in which we can touch people’s hearts. Natural phenomena are highly relatable and can be transmitted in a strong, straightforward way, so that makes them an incredibly good medium for conveying the new perspectives we wish to express.

Methods of expression and elaborate designs.

-There are many signs of experimentation and testing in the studio. Are the two of you making these kinds of test products?

Ando: Yes, that’s right. We, along with the other members of “we+” are constantly doing experiments. People have a strong tendency to imagine someone sitting at a computer making schematics when they think of designers, but in our case, we often take a material-driven method to our design work, so I think we spend quite a lot of time actually using our hands.

When it comes to creating something, making the entire thing from start to finish like the craftsmen of old did was commonplace, but with industrialization the division of labor has advanced, and designers are now only involved in a limited part of the process. Despite designers being the ones who forge the base of the creation, in reality it’s somebody else who actually creates the thing in question. This is something we always felt was strange...

One of the many traces of experimentation that litter the studio. Photo: Hiroaki Sagara

Hayashi: Designers are often perceived as just a functionality that draws a design and doesn’t actually have a view of the bigger picture of the creation. However, we want to place ourselves in the center of the creative environment and have responsibility for what we create. So, whether it be an installation or a product, we want to go through the experiments and create the base, develop and complete the entire thing ourselves. Of course, there are times when we ask others to complete the final product for us, but generally speaking we insource the entire process.

-I see. I imagine that by involving yourself in every aspect of the creative environment, you can express 100% of what you want to convey.

Ando: That’s right. By involving ourselves in every step of the process, we can carefully plan the relativity between the concept and method of expression. Simply creating something without a second thought, and making something come together as a creation with meaning, are very different things.

-What does “we+” consider to be most important in order to create the best relationship between method of expression and concept?

Ando: I think that would be changing the expression and the concept. Using the concept to drive the creation, then using the expression, then the concept again... repeating this process. By doing this, we often find ourselves arriving at a completely different creation to what we have originally envisioned. No project ever goes exactly as we conceived them in our heads. It’s like the expression and concept are a blur while we work, and at the very end it suddenly becomes clear.

Hayashi: In large companies and the like where the scale of a team is quite big, the flow is kind of fixed in place and I feel it often functions like a one-way street. It’s usually something like research→design→prototype creation→final product, and once it gets into motion they often don’t turn back. But in our case, the flow isn’t set in stone. As Ando mentioned, this thing where the expression and concept pulling each other along occurs, which results in things getting messy all the time... However, I think it’s because we choose not to be particular about the design process we take, that the expression and concept end up with an equilibrium that we are happy with.

Having fun and trying, even if the path ahead is unclear.

-I’d like to ask you about a more specific aspect of design. I believe the concept behind “we+” is “us plus something else,” so how do you go about a project when it involves a team?

Ando: The range of things we can make is limited if it’s just Hayashi and myself, so we really try to keep the mindset of teaming up with people who have the right skills. Specialists naturally know more about their field and know lots of great solutions. When we collaborate, we always do so on an even playing field and progress forward as a unit.

FLUX (2019) Created with the help of a specialist in fluid development and water flow control. Photo: Daisuke Ohki

-How do you find the people that you collaborate with?

Ando: We often work with people we already know, but sometimes also with people we have absolutely no connection with. Sometimes we’ll just find them on the internet, get in touch and approach them.

Hayashi: When we suddenly approach someone, it’s always kind of lucky if you can come across the types who like to just dive into something. People who want to take on challenges or enjoy new things don’t just offer their technical prowess, but also new ideas and things like that which can often drive a project.

-So, there are times when you approach people you’ve never met. I imagine that means you would start working together at a point when the goal of the project is still unclear. How do you keep everyone motivated?

Ando: I think it’s important that first and foremost we’re enjoying what we’re doing. I feel that more so than taking a mature, intelligent approach, that getting into it with a kind of honest and innocent mindset is what makes it exciting, which is something the other people involved can feel, too. Just listening to a specialist talk about their craft is exciting, so I naturally end up feeling that exact way being all “Oh, man that’s amazing!” while I listen (laughter).

Hayashi: Even for things that are commonplace to a specialist, it’s not necessarily the case for us, so we make a lot of discoveries. A project becoming better quality with the addition of those specialists’ techniques, or the direction of our output taking on a new path are the best things about doing collaborative work.

-Through your collaboration with various people outside of the studio, I imagine you’ve acquired a wide range of knowledge, but how do you go about selecting the materials and technology to use for creating something? Do you research these things after deciding what to do, or do you have like a stock of ideas...?

Hayashi: We always share information on what materials we have or come across. Also, we sometimes go to large expos dealing in materials and the like. You can come across quite rare things at these, and even if you don’t use the materials directly, they are still quite meaningful as they can often give you hints.

Ando: We also often buy materials that we’re curious about via Amazon and services like that.

Hayashi: True. One thing that often happens is someone comes up with an idea, and a few moments later Ando finds it online and we end up buying it. We’re actually incredibly analog. We spend about 90% of our time on a project going through trial and error to work out what we’re after (laughter).

Ando: The mindset and method of what we do is basically like an “elementary school science experiment.” However, I think that very stance of trying something even if you don’t know if you’ll use it or if it will even work, is really important. Also, with our way of doing things we have a lot of left-over materials that go unused, but on many occasions, they get to see the light of day again when they are a match for a different project, which is another thing that’s quite interesting.

Ascertaining the context of a location and displaying relatability.

-Your creations are sometimes displayed public, for example in the windows of commercial facilities or outdoor installations. How do these public spaces affect your creations?

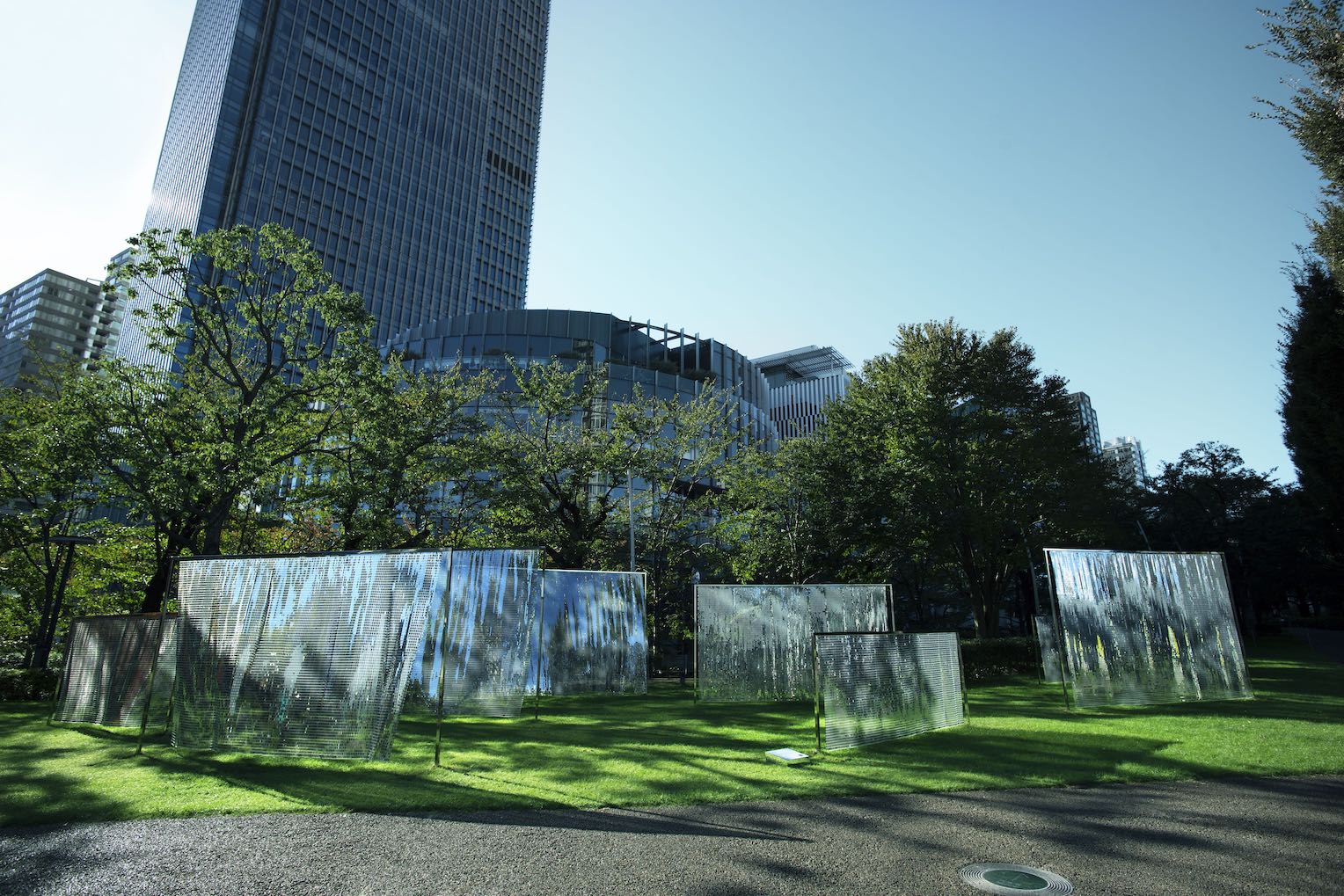

Hayashi: For example, the piece we worked on for Roppongi Midtown last year was our first outdoor installation. We spent so much time thinking about “what is it that we can only do here?” We visited the location between 20 and 30 times with all the stuff we were going to use, because we wanted to think about how we could utilize the space as there were limitations on things like rain, wind, and light.

Swell (2018) Outdoor installation in the Tokyo Midtown garden.

Ando: The context of a location is extremely important. What we did in Roppongi, for example, just wouldn’t work if we tried it somewhere out in the mountains. The implications of an expression change quite a lot based on who sees it, the geographical features, the physical surroundings, and what kind of location it is. The same goes for a window display, so we have to think about the characteristics of the area itself and how we can catch the attention of people passing by. People are drawn to things that surprise them or things then can relate to, so it’s easy to catch people if you show them something they’re familiar with, but from a fresh perspective. From a creator’s perspective “displaying relatability” is what makes it exciting to exhibit a creation in a city with lots of people going back and forth.

-I imagine some ingenuity in the way you convey things is needed in order to get the attention of someone just passing by.

Hayashi: That’s correct. For installations in a public space, the assumption is that an unspecified large number of people will view it, so we express our contemporary designs in a more simplified way. As such, the vector of expression ends up being different to that of pieces which would be displayed in a gallery like the chair we talked about earlier, but in both cases the idea of “offering alternative perspectives” is still at the core.

The beauty of Yokoyamacho is “noise.” We want to discover expressions only this area can offer.

-I understand you’ve just relocated to Yokoyamacho last summer. What do you think of the area?

Ando: It has a really strong sense of local community. There are new facilities mixed in with wholesalers and eateries that have been around for a long time. There’s a unique kind of chaos that makes it interesting.

Hayashi: My first impression was that there are a lot of mystery shops (laughter). There are shops that just make you wonder how they are getting by, and also a kind of Southeast Asia feel, which just makes this area quite the curiosity. I used to prefer places with a more curated feel like Nakameguro or Daikanyama, but as I get older, I’ve started to take a liking to these unique kinds of areas, so perhaps that just makes my attraction to this area stronger.

Ando: Also, having so many wholesalers around and Akihabara close by makes it easy to buy materials. It’s an area with a foundation in craftsmanship, so for creators like us this area is something we really appreciate.

Ginza and Tokyo stations are also easy to access, which helps when it comes to meeting people for business.

-Do you have any ideas for things you’d like to try in this area?

Ando: One thing I’ve been interested in what you could call the “noise” of the city. Tokyo is overall really organized, but within that organization are things that slip through. There’s always something that doesn’t fit, something that’s bursting out. For example, there are always empty cans that didn’t fit in a vending machine trash box, but for some reason they’re lined up neatly on the ground, or new and sophisticated buildings that have old, rundown signs next to them that just feel out of place. I feel drawn to these kinds of inconsistencies, or “noise,” and find artistic inspiration in them.

In that sense, Yokoyamacho is a treasure trove of noise (laughter). I feel it would be really interesting to do exhibitions in places that make people go “why is this here!?” I think on a daily basis about how good it would be to do something around here in one of the buildings with lots of wholesalers in it.

-You mean like switching to the side that creates the “noise.” That would be quite interesting.

The wholesaler street where the office of “we+” is located.

-At the moment, do you have any things you want to challenge or collaborations you would like to take part in?

Hayashi: I’d like to do something with scientists or physicists, someone who does research specialized in that kind of domain. A lot of our ideas come from childlike scientific experiments, so I’m interested in how someone who has pursued these things deeply sees what we do. I think collaborating with a researcher would add a new perspective and bring greater depth to the project.

Ando: In the sense of digging further into context, working with a historian could be good, too. By researching the history of what we’re trying to express, we could find knowledge and techniques that were once lost. Including these in a modern creation could be quite interesting. Either way, we want to work more and more with people who have different perspectives to us in the future.

Interview: Mitsuyo Demura (Konel) Words: Minako Ushida (Konel) Photography: Daisuke Okamura

we+

A contemporary design studio that creates new perspectives and value through methods of expression grounded in research and experimentation. A member of design galleries such as Gallery S. Bensimon (Paris) and Rossana Orlandi (Milano). In addition to exhibiting their work both domestically and overseas, the members of the team and their varied backgrounds use their individual strengths and knowledge acquired from daily research to involve themselves in projects such as installations, commissions, branding, product and visual development for various companies and organizations. “we+” has received numerous awards domestically and internationally, such as ELLE DÉCOR YOUNG DESIGNER OF THE YEAR, KUKAN Design Aware (Gold), DSA Design Award (Gold, Bronze) and so on.