The Future of Beauty According to a Nihonbashi Insect Cuisine Restaurant.

The Future of Beauty According to a Nihonbashi Insect Cuisine Restaurant.

A unique restaurant started business in a corner of Bakurocho, Nihonbashi on June 4, 2020 (phonetically “insect day” in Japanese). Its name is “ANTCICADA,” the insect restaurant. It was the focus of major media attention and a crowdfunding effort even before opening, while developing cricket ramen and multi-course meals using insects. Two months since its opening, we wondered what its owners were up too, and how they were feeling. For this issue, we spoke with Join Earth Co., Ltd. representative and ANTCICADA manager Mr. Yuta Shinohara about the future of food they are targeting with the restaurant’s cuisine.

It all began with the debut of insect cuisine.

-First, could you tell us about the events leading up to the restaurant’s opening, and your current projects?

We genuinely began imagining “ANTCICADA” the restaurant with the “Cricket Ramen” project that launched in 2018 at Shibuya’s 100BANCH (a facility that supports open innovation). We worked on catering and pop-up storefronts, lectures, and writing and so forth while developing products and preparing to open, initially, and each day was overwhelming. Then last year, we crowdfunded an effort to open a standing restaurant, got twice the support we aimed for, and were finally able to open up in Bakurocho this June. The name is a combination of “ant” and “cicada,” and we currently serve multi-course insect meals (with drink pairings) on Fridays and Saturdays, and cricket ramen on Sundays. We also sell some products online.

-What first got you interested in insects?

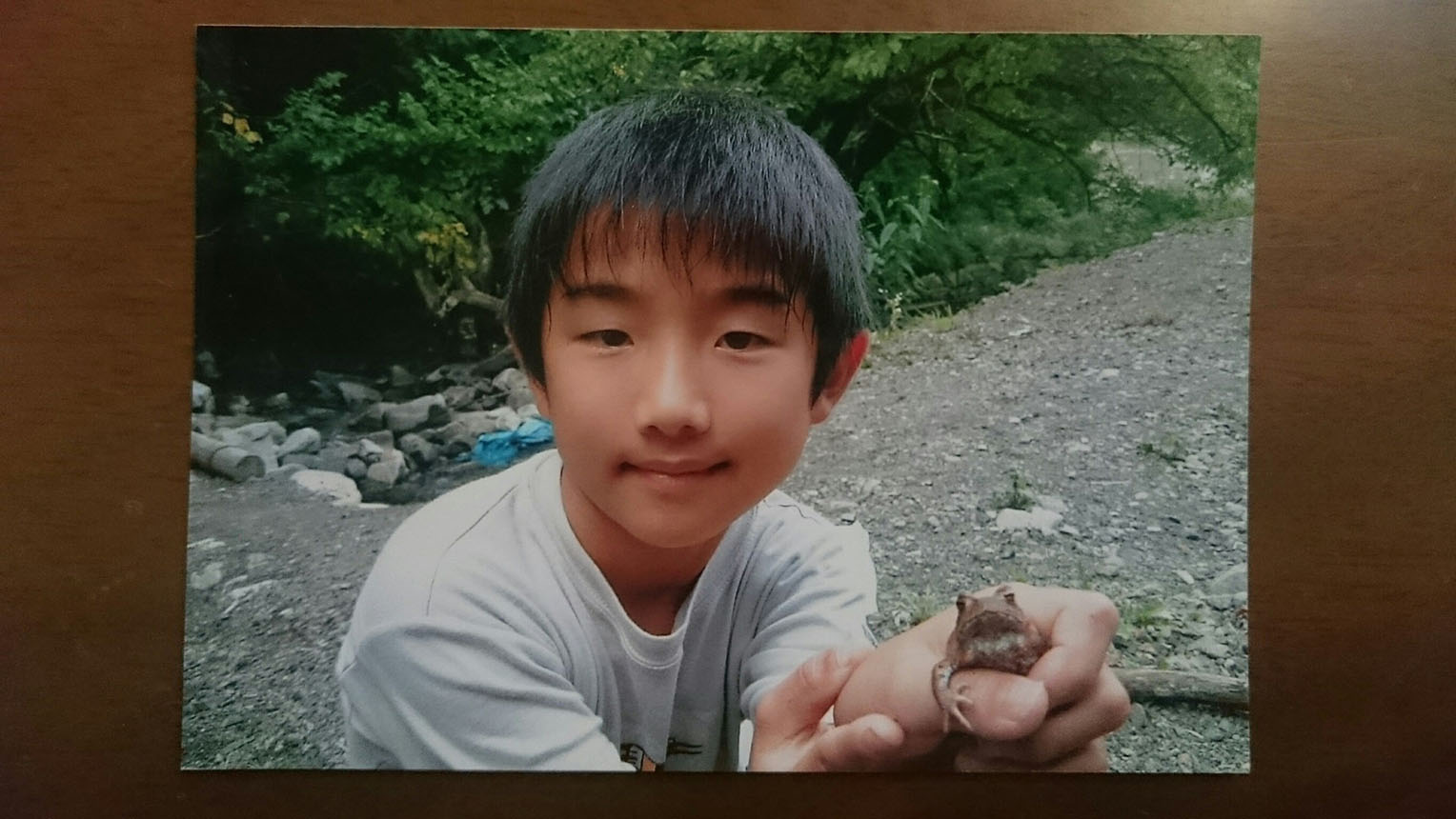

I’m from Hachioji, and always loved playing in natural settings as a kid. I ate all sorts of things and tried keeping others as pets back then, when I’d watch the fruit in the trees, the grass, and the bugs nearby. I think all aspects of nature are amazing, but the world at large seems to have a negative view of insects for some reason, doesn’t it? My kindergarten teacher got mad at me once for bringing a lot of bugs to school, and they’re used as a threat in games with famous people on TV… Why are they viewed as such a menace? I always wondered, as a child. My view and the world’s view were never more different than when it came to insects. With that as a backdrop, I felt driven to show people more of the good sides of insects, which led me to work on insect cuisine projects.

But there was a struggle to get people to embrace that sort of positive view. I used to worry that I was weird because of how different my perceptions were from those around me, as a kid. I didn’t just like insects; I actually ate them, and couldn’t mention that to anyone… So I hid it.

Mr. Yuta Shinohara, ANTCICADA’s representative

-Do you remember when you first ate an insect? What made you want to?

I first ate one at age four, but as for why, all I can say is “because there was a bug there.” (Laughter) I didn’t have any deep reason or resolve, and I think I just put it in my mouth out of fascination. I don’t really remember that clearly, though.

But I do have a clear memory of when I found myself fascinated by insect cuisine. It was when I ate a hairy caterpillar in a park one time. It was as sweet as sakura-mochi rice dumplings, and a very refined flavor without undertones or bad odors. I was amazed at how different it was from how it looked. It probably had that flavor because it had only ever eaten sakura cherry tree leaves, and you get a direct sense of what a caterpillar has eaten and lived through when you eat it. You can sense its whole life. It gave me a profound sense of the parts of nature cycling their way up to me, and was a very moving experience.

-Is there any special story that led you to try to communicate that appealing side of insects to those around you?

I “came out” about eating insects when I was 19, at the end of my freshman year of college, after the FAO (UN Food and Agriculture Organization) Report was published that spring. The report cited insect cuisine as a source of hope for the future for two reasons: first, because it’s highly nutritious, and second, because it is highly sustainable and conserves resources. With a powerful organization reporting it officially, the media covered the information as something impactful. I felt like I had suddenly gotten this amazing support for my side, and decided to be brave and come out about eating insects.

-That sounds like it would be stressful. What sort of responses did you get?

I didn’t have any close friends to open up to directly, so instead I treated it as a sort of distant thing, casually posting on Facebook that “apparently insect cuisine is in the news. I eat them, too,” while sharing an article on insect cuisine (laughter). I got a lot of negative comments, with people who saw it saying “why?” or “I don’t get it,” and “that’s gross, don’t post that.” I imagined there would be some of that, but it was quite hurtful.

But out of all of them, one person sent me a message saying “I’m intrigued, so let’s go catch insects sometime and eat them.” So we went to the mountains together, cooked the bugs we caught there on the spot, and tried them. They were surprised how much they enjoyed it, saying “I had no idea insects were so tasty!” That made me really happy. It was the first moment in my life that I had shared something I liked and it had gotten through to the other person. Looking back on it, I feel like all my projects after that started from that point.

a picture from when Mr. Yuta Shinohara was young (Image provided by: ANTCICADA)

An “experimental lab” created alongside customers.

-That experience connects with how you serve customers insect cuisine now, doesn’t it?

Yes, it does. After that, I started to see more and more people getting interested in insect cuisine, and started to want to serve them insect dishes that would exceed their expectations. But I didn’t know anything about cooking, so all I could do was mutter on social media about how this bug tastes like this, or how they were good to eat. And as I kept at sharing on social media, even as frustrated as I was, a chef that saw it contacted me and put me in touch with people to collaborate with. “Ramen Nagi” – my collaborators in developing cricket ramen – was one of those introductions. “Ramen Nagi” let me study how they make great ramen from scratch, and helped me out a lot.

After that experience, I was finally able to cook well enough to put insect cuisine on another level. And I resolved to open the proper restaurant I had always wanted to so badly.

The ANTCICADA team. All members are in their 20s and put their specialties to use on the job (Image provided by: ANTCICADA)

-Your restaurant’s menu is heavily focused on multi-course meals, as well as cricket ramen. How did you decide what would go on the menu you serve?

Naturally, my desire to build a place where lots of people could learn about the appeal of insect cuisine was part of the backdrop to why I wanted to open a restaurant. But I felt like just operating as a normal insect cuisine restaurant would lead to a “restaurant where weird people who love insects gather.” So I decided to serve an easy-to-grasp menu that lots of people would be interested in, wanting to make it easier to take the first step into insect cuisine. And the “cricket ramen” we had served at events in the past fit perfectly with that menu.

And we also offer the multi-course meal menu for people who want to get more deeply into insect cuisine, after getting intrigued by the ramen.

The editorial department also sampled the cricket ramen. It was delicious and refined ramen, with a fragrance similar to shrimp stock

-How have customers responded, now that it has been a bit over a month since you opened?

A lot of customers say the restaurant is fun, and overall the reception was positive. I really got a sense for how having a location like a restaurant creates more of a conversation with customers than I expected. I think it’s about as important that people learn the story behind our food as it is that the food is good. So I explain bugs carefully when I talk with customers. I want to create opportunities to change their preconceptions about bugs.

In fact, a lot of our repeat customers who visit each week for cricket ramen actually started out hating bugs. But people who hate them experience a greater change in their preconceptions when they eat our food and hear our story. One customer was terrified to try it, then reacted like, “how can it be delicious?” They eventually challenged themselves with single dishes and drinks and so forth, little by little, and ended up a fan who agrees that “bugs are impressive.” They tell me they think the bugs they see by the roadside are cute, now. (Laughter)

タガメジンのコピー.jpg)

A craft gin made using giant water bugs, which was developed in partnership with the Takumi Joryujo distillery in Gujo, Gifu prefecture (Image provided by: ANTCICADA)

-Being able to communicate with customers lets you convey a deeper understanding of the appeal of insect cuisine, doesn’t it?

Yes, it does. Eventually, I want to make this restaurant into a place we build up while listening to customer suggestions, instead of just a restaurant where chefs serve food in a one-directional way. The ideal restaurant is like an open experimental lab where you undergo a process of trial and error, while allowing leeway for the next possibility. For example, we currently have an issue with how to use the empty exoskeletons of the 9,000 crickets we use when making the soup for our cricket ramen. And we’ve received all sorts of ideas from customers about that. People have suggested making them into senbei rice crackets, or mixing them into chocolate to make it crunchy, and so on. We’ve gotten a lot of unique proposals.

When I allowed for deeper communication like that, I found myself interacting more with customers outside the restaurant, after they got interested in insects. Most recently, I’m planning a vacation to tour a silkworm farm in Yamanashi with about 15 customers, and have been looking forward to it. That kind of sign that we’re forming a casual community makes me very happy.

Investigating the potential of insects alongside a crowd of collaborators (Image provided by: ANTCICADA)

A perspective on flavor for the future of insect cuisine.

-Your projects are definitely part of this, Mr. Shinohara, but wouldn’t you say it feels like the entire insect cuisine industry is energized?

Food issues grow more severe each year due to the explosion in population, and the view that insect cuisine will save us is gaining strength. For example, it takes an enormous amount of feed, water, land, labor expenses, and time to produce meat, while it takes much less of each for insects, with crickets becoming edible about a month after the eggs are laid. While producers were rare before, they’re steadily growing in number, and the product development field is heating up little by little.

-MUJI was in the news this year for launching “cricket senbei,” weren’t they?

Yes, they were. They’re using crickets we developed jointly with Tokushima University, and having a company like MUJI market it to the general public has a major impact, as you’d expect. It’s priced affordably at ¥190, and I think it’s a good thing for us and a turning point for the spread of insect cuisine to the general public.

But one thing holding back the whole industry right now is the debate on “using insects as ingredients.” While it’s great that insects are getting attention as a meaningful food source for society, our basic concepts right now involve “how to use bugs without revealing what they are,” as an odd ingredient. I feel like they’re not recognized as a food on their own. The stance is to conceal them with colors and flavors, and give in to the idea of using them as a substitute for other ingredients.

That’s precisely why we’re researching ideas out of a drive to add a perspective on “flavor” to the world of insect cuisine. If you’re going to eat bugs, the people preparing and eating them will both be happier if you focus on how they’ll taste best. Just like any other ingredient.

An example of a course from the restaurant’s meals. They serve dishes overflowing with new ideas (Image provided by: ANTCICADA)

Respecting the old, while shining a light on new perspectives.

-Was there any reason you chose Bakurocho, Nihonbashi as the site to open your restaurant at?

There were two. First, the building’s owner’s strong desire to “draw all sorts of interesting people to Bakurocho and liven up the area” appealed to me. And the other was that when I walked through the city, I could feel that there were compatible people we would get along with here. Appealing startups and restaurants were gathering just like the owner wanted, and that made me want to get actively involved with the city.

This buzzing atmosphere as Bakurocho evolves is perfect for us, since we were looking for a place to spread insect cuisine “culture” from over the medium to long term. And since Nihonbashi used to be the crossroads of the five highways of medieval Japan, we’re another cycle of its story of sharing new ideas with the world. I really like that.

-Nihonbashi has prospered historically as a city of food. Does it seem like you’ll set off a new trend in the city’s food culture by adding in a new genre for everyone, with insect cuisine?

Yes, I really want us to be a presence that creates that sort of trend. My one condition is that while people tend to think of insect cuisine as new, it’s actually a primal food culture that we’ve had since ancient times. Insects were an early protein source for humanity, and the insect tsukudani soy-boiled preserves we know as traditional country food in Japan was eaten across the nation. But it’s a fact that people don’t want the traditional form of insect cuisine anymore, and it’s hard to say that rural tsukudani restaurants are popular, even having spoken with them.

Still, I think we can shed a light on new approaches in the modern era; ones that aren’t like the old tsukudani style. I want to fully respect that food culture and carry on its positives, but I think that when it comes to showing a new side as “an extension of history,” there are always ways to update traditional foods.

-Do you have any specific ideas in mind?

For example, we really are working on making tsukudani. It turns out that tsukudani originated from Tsukuda, in Chuo City, so I feel a connection with it. But we’re new and don’t know traditional ways of making or selling it. So for example, I’d love to collaborate with an established Nihonbashi tsukudani business to find the next possibility for the dish. We could approach via changing how it looks, and then work on how to convey the true essence of the tradition.

An ANTCICADA original insect tsukudani. They offer three varieties: cricket, silkworm, and locust (Image provided by: ANTCICADA)

Food isn’t work; it’s an adventure.

-Could you share your thoughts about the role and ideal forms of food in the coming era?

I feel like no natural beauty or rare experience can truly compare to the emotional impact of food. “Eating” connects us to all of our senses and the natural world, and is “a personal experience” of facing ourselves and the natural world. But I feel like in this era, it’s becoming “a social experience” that is easily influenced by the values of those around us. For example, when we see a place we like with a rating of 3.0 on a review website, we wonder if it’s actually not that good. And in the reverse, we feel like food tastes better if it’s highly rated. I think that’s where we can see the phenomenon.

What tastes good varies by person, and I think the ideal is to have your own standards, free from preconceptions. And I hope we can touch off a new, free way of enjoying food, since insect cuisine really has no existing standards. Our slogan is “food isn’t work; it’s an adventure.” I think that adding more free and adventurous elements and “a perspective on the world” to food can make our lives a bit richer.

And I want to put in the time to spread that idea properly, through our work.

-Finally, could you share any future challenges that you hope to take on?

I want to collaborate with local people, going forward. Since we’re steadily building connections with customers, the next step is to create something with the local Nihonbashi residents. I feel like there are all sorts of possibilities aside from just food: fashion insects, insect art, and so on. The Nihonbashi area has people in diverse industries new and old, so I want to use the full potential of our location here. If anyone in Nihonbashi feels like they don’t have any novel new moves to make, we might be able to help out. Please get in touch!

Interview and text: Minako Ushida (Konel) Photography: Daisuke Okamura

ANTCICADA

An insect cuisine opened in Bakurocho, Nihonbashi this year as “an inquisitive restaurant that loves the earth.”

The restaurant handles originally-developed products and menu items that use insect characteristics, headed up by the world’s first “cricket ramen” – with two types of cricket soup. ANTCICADA takes on the issue of insects as an ingredient head-on, and seeks to serve appealing insect cuisine unlike anything seen before.

https://antcicada.com/

Online shop

https://antcicada.shop/